Part Ten — One Hundred Years of Michigan Work in Art: 1850 to 1950

Marrying work and art “ten minutes at a time, when time was available”

When material from Michigan industry becomes the materiel of Michigan art, the marriage of art and work is complete. And this union often produces delightful progeny.

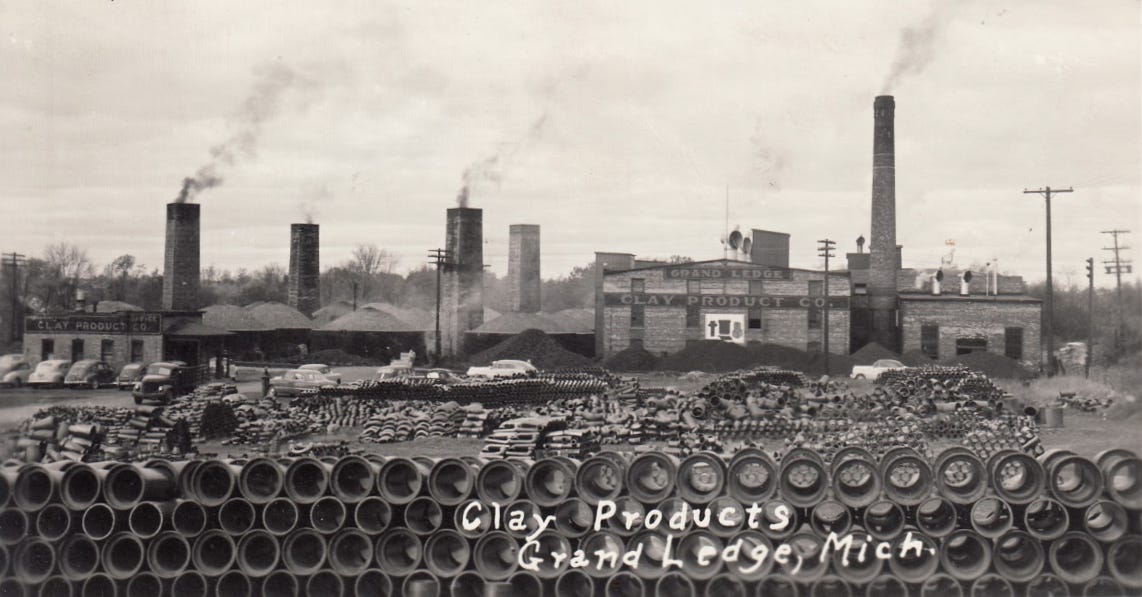

When traditional art materials were unavailable or beyond the means of worker-artists, some imaginatively—and occasionally surreptitiously—turned workplace scrap into artistic media. Leftover clay from the manufacture of sewer tiles in Grand Ledge was crafted into figures, vases, masks, etc.[i]; dried paint from auto spray booths (known as “Fordite” or “Detroit Agate”) was transformed into jewelry; injection-molded plastic into sculpture;[ii] and scraps of rope were transformed by marlinespike artisans into beautiful as well as practical work tools.[iii] These occupational folk art pieces are also known as “homers”.[iv]

While most homers did not directly depict workplaces/processes, they did showcase worker-artists’ inventive time-management, vocational skill, and intimate familiarity with their work material. In the gaps between Fleetwoods or Fairlanes, assembly-line-artists welded scrap steel into folk art.[v] “Ten minutes at a time, when time was available,”[vi] textile worker-artists pieced quilts from scraps of silk shoe-lining and trim scraps from corsets or shirts.

Appropriating not only material from their employers but tools and work time, Michigan’s famously recalcitrant workers found that the “illicit nature” of the process enhance[ed] their satisfaction with it.[vii] Homers helped to humanize an increasingly inhuman industrial landscape and gave back a small measure of control to their creators.

“The human desire to create,” writes MSU Museum’s director emeritus C. Kurt Dewhurst, “occurs not only in surprising places, but in surprising shapes.”[viii] This occurrence is perhaps not quite so surprising in a state such as Michigan, where the shape of its art has always been inextricably tied to the place of its work.

Part Ten concludes the series “One Hundred Years of Michigan Work in Art: 1850 to 1950.” Look for more essays on the topic of Michigan work in art, however, as it is an ongoing and compelling part of Michigan’s contribution to American art.

[i] Marsha MacDowell and C. Kurt Dewhurst, “The Sewer Tile Clay Pottery of Grand Ledge Michigan” Northeast Historical Archaeology 9, no. 1 (1980), 40.

[ii] Yvonne Lockwood, “The Joy of Labor,” in Michigan Folklife Reader, eds. C. Kurt Dewhurst and Yvonne Lockwood. (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1987), 266-67.

[iii] LuAnne Gaykowski Kozma, Janet Crofton Gilmore, Jay C. Martin, Marlinespikes and Monkey’s Fists: Traditional Arts and Knot-tying Skills of Maritime Workers (East Lansing: Michigan Traditional Arts Program, 1994) 6.

[iv] Lockwood, 264.

[v] Lockwood, 263.

[vi] Marsha MacDowell and Ruth D. Fitzgerald, eds., Michigan Quilts: 150 Years of a Textile Tradition (East Lansing: Michigan State University Museum, 1987), 44.

[vii] Lockwood, 263.

[viii] C. Kurt Dewhurst, Grand Ledge Folk Pottery Traditions at Work, (Ann Arbor, UMI Research Press, 1986), xvi.

Another informative piece of history. Thanks