In ballads, if not always in actuality, Lakers (as Great Lakes seamen are called) were “all gallant lads”[i] whose “jovial hearts of oak [stood] many a bitter squall,”[ii] and who remained “each man at his station, [with] brave hearts and true”[iii] even as the pumps failed and the seams sprang. They were the boys and chums of the era’s young-adult adventure books—the Iron Boys on the Ore Boats (1913), The Go-Ahead Boys on Smugglers’ Island (1916), and The Darewell Chums on a Cruise (1909). They were the “surefooted and strong” sailors in Jane Rietveld’s better-written young-adult novel, Great Lakes Sailor (1952). “Courage,” her protagonist whispers to himself: “It takes courage to be a sailor on the Lakes.”[iv]

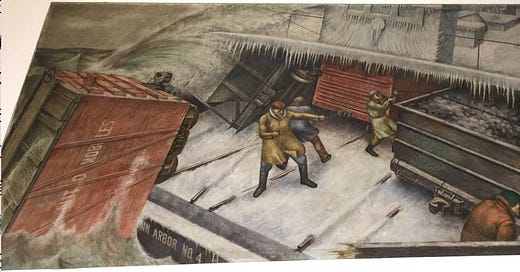

Detroit-born artist Henry Bernstein (1912-1962) captured the real-life heroics of the crew of the car ferry Ann Arbor No. 4, which foundered off Frankfort harbor on Valentine’s Day, 1923. Funded by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Section for Fine Arts, his 1941 mural depicts the ferry’s aft deck, sheathed in ice. Five seamen in purposeful, though not frantic, postures are attempting to secure rail cars on the wave-swept deck. A fictional foreshadowing of this event occurs at the end the 1917 novel The Indian Drum by William MacHarg (1872-1951) and Edwin Balmer (1883-1959):

The roar and echoing tumult of the ice against the hull here drowned all other sounds. The thirty-two freight cars…tipped and tilted, rolled and swayed…. The deck was all ice now underfoot…to liberate and throw overboard heavily loaded cars from an endangered ship was so desperate an undertaking and so certain to cost life that men attempted it only in final extremities….a box car, heavily laden—swayed and shrieked with the pitching of the ship.…the men with pinch-bars attacked the car to isolate it and force it aft along the track. It moved slowly at first…sharply with the lift of the deck, it stopped, toppled toward the men who, yelling to one another, scrambled away… while the water washed higher and higher.[v]

Owosso castle builder and adventure writer James Oliver Curwood (1878-1927) portrayed work on the Lakes—in potboilers like “The Lake Breed” (1905) and the “The Fish Pirates”(1909—as a “thrilling” mélange of “romantic, long-haired women and adventurous men, mutinous crews, pirates and smugglers and sinking freighters.”[vi] In reality, much shipboard work was manual, boring, dangerous, and exhausting. Journalist and former freshwater deckhand Jay McCormick (1919-1997) used the adjective “tired” repeatedly throughout his 1942 novel November Storm [vii] to describe individual crew members on the freighter Blackfoot. McCormick never varies the word with synonyms or modifies it by adverbs, rather the word drones throughout the narrative, leveling and connecting all members of the crew, from stoker to captain. Rather than identifying with their Sisyphean work, individual crew members focus affection on their work tools: the engineer is said to “tenderly” slow the freighter’s “faithful engines”[viii] and the cook to “apologetically”[ix] pick up the kettle he’s kicked. The stoic captain is brought close to “raving madness when a tug…banged [the Blackfoot’s] lovely sides against a cement dock.”[x]

McCormick’s contemporary, the painter David Fredenthal (1914-1958) also worked on Lakes freighters as a young man. Among the works he created for the 1948 travelling exhibit “Michigan on Canvas,”[xi] is a twelve-panel painting called “Lake Freighter.” Fredenthal fills the panels with muscled crewmen handling massive hawsers, securing heavy hatch covers, and unloading cargo. The bodies of the shirtless young men appear plated, like the steel bodies of their ships; their hands and shoulders are drawn disproportionately large, emphasizing the extreme physicality of their labor.

Red Iron Ore (Trad.) performed by Bob Gibson.

Part 3 of this series will continue exploring “The Michigan Worker Afloat,” focusing on Great Lakes fishing industry.

[i] Traditional ballad, “The schooner Thomas Hume” in Windjammers: Songs of the Great Lakes Sailors, eds. Ivan. H. Walton and Joe Grimm (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2002), 197.

[ii] Traditional ballad, “You Pretty Girls of Michigan” in Walton, 101.

[iii] Traditional ballad, “Lost on Lake Michigan,” in Walton, 174.

[iv] Jane Rietveld, Great Lakes Sailor (New York: The Viking Press, 1952), 48.

[v] William MacHarg and Edwin Balmer, The Indian Drum (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1917), 266-293.

[vi] Ed Demerly, “James Oliver Curwood” in Encyclopedia of American Literature of the Sea and Great Lakes, ed. Gidmark (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 105.

[vii] Called by Victoria Brehm the “finest novel written about maritime life on the Lakes” in Sweetwater, Storms, and Spirits, ed. Brehm (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991), 295.

[viii] Jay McCormick, November Storm (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, and Company, 1943), 301.

[ix] McCormick, 286.

[x] McCormick, 170.

[xi] In 1946, Detroit’s J. L. Hudson Company commissioned ten nationally known artists to “portray artistically to the people of Michigan the assets of their great state.” Over half of the 100 hundred paintings submitted to the “Michigan on Canvas” project were scenes of work and workers. Laurence Schmeckebier, Zoltan Sepeshy: Forty Years of his Work (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University School of Art, 1966), 35.

Nicely done