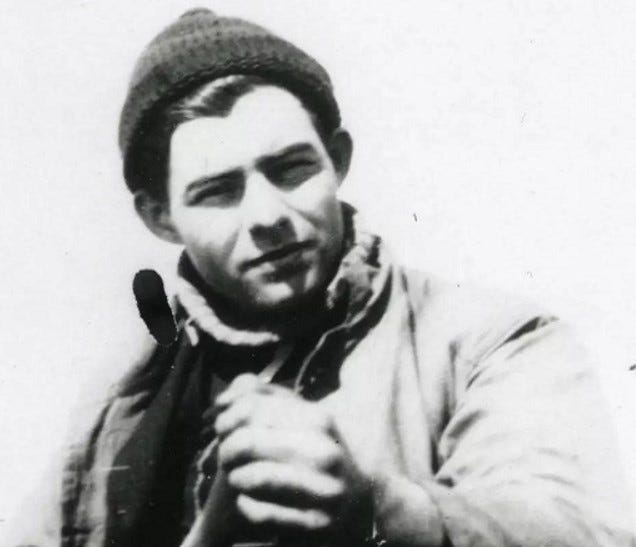

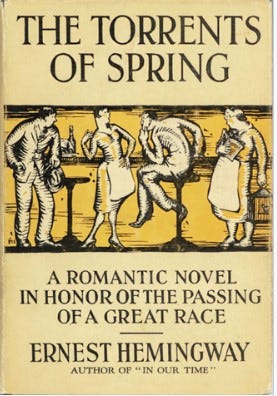

In early December of 1925, Ernest Hemingway sent off the manuscript for his Petoskey-based novel, The Torrents of Spring, to his New York publishers Boni & Liveright. Their Christmas present to him several weeks later was a rejection slip.

He couldn’t have been happier.

The book was a bit of a slap-dash affair, written in slightly under two weeks. And Hemingway was eager to give Boni & Liveright the slip. He had his eye on a different publisher—Scribner’s—who eventually published the work in May of 1926. It was reviewed by The New York Times (June 13, 1926), which called it “literary vaudeville” for its hammy (if stinging) parody of Sherwood Anderson, whose literary style Hemingway found especially annoying.

As the novel opens, its two main characters—Yogi Johnson and Scripps O’Neil—are looking out onto the yard of a piston-pump factory in Petoskey where they work. The yard is filled with crated pumps, snow-covered and waiting in a kind of suspended animation for spring. The factory workers are similarly suspended, by the cold and by the monotony of their work:

“Once the spring should come and the snow melt, workmen from the factory would break out of the pumps from piles where they were snowed in and haul them down to the G.R. & I. station, where they would be loaded on flat-cars and shipped away. Yogi Johnson looked out the window at the snowed-in pumps, and …thought of Paris…That was all behind him now. That and everything else.”

Train-tracks, the Great War, and the warm chinook wind run throughout the novel as metaphors for possibility and escape. The pumps are lucky—with the spring thaw, a flat-car is their ticket out of the factory and out of town. For the factory workers, their war service is looked back upon with equal fondness and horror: primarily to contrast with their current state. Like the spring and the trains, the War was their ticket out. What they didn’t know was the ticket was round-trip.

Initially, Scripps had hoped that factory labor would ennoble him: “Picasso had worked in a cigarette-factory in his boyhood…Emerson has been a hod-carrier…Why shouldn’t he, Scripps O’Neil, work in a pump-factory?” (23). Instead, the work becomes a “hideous nightmare,” its promise dissolving into confinement and disappointment:

“Men naked to the waist took the pumps in huge tongs as they came trundling by on an endless chain, culling out the misfits and placing the perfect pumps on another endless chain that carried them up in the cooling room. Other men…broke up the misfit pumps with huge hammers and adzes and rapidly recast them into axe heads, wagon springs, trombone slides, bullet molds.”

The undoing of all this surreal productivity (in the northland, where winter never leaves soon enough) is the advent of the chinook, a warm spring wind, even a whiff of which will unhinge the pump-factory men, as the factory foreman well knew.

“It’s a real chinook wind, Yogi thought. The foreman did right to let the men go. It wouldn’t be safe keeping them in on a day like this. Anything might happen…When the chinook blew, the thing to do was to get the men out of the factory. Then, if any of them were injured, it was not on him. He didn’t get caught under the Employer’s Liability Act. They knew a thing or two, these big pump-manufacturers.”

The narrative continues, delightfully unhinged, when Scripps is introduced to the “greatest living pump-maker”—an old gentleman who, Hemingway tells us, carves the steel pumps with a small knife, creating stars like the “Peerless Pounder” that win “big international pump races” in Italy. For the remainder of novel, love, books, betrayal, and sexual rebirth stumble after each other down the road out of Petoskey on the heels of the lucky pumps.

Torrents may not be a great novel, I suppose, but for those of us who can’t get enough of Hemingway-in-the-Northland, it’s well worth the read

.

Wonderful insights into the Torrents of Spring, calling attention to the metaphors for life (both then and now)... Even war offers hope for escape from the mundane and the hero is an old gentleman who was the "greatest living pump maker." Dreams which make life bearable clash with reality. I am not familiar with this Hemingway novel, but your review certainly has me intrigued.